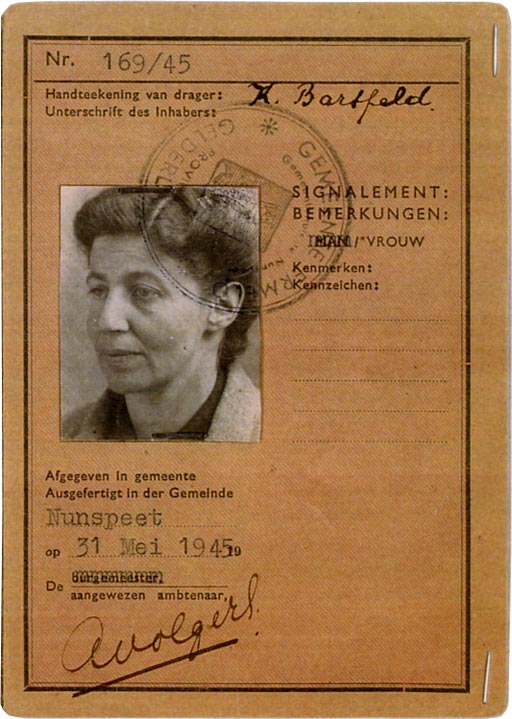

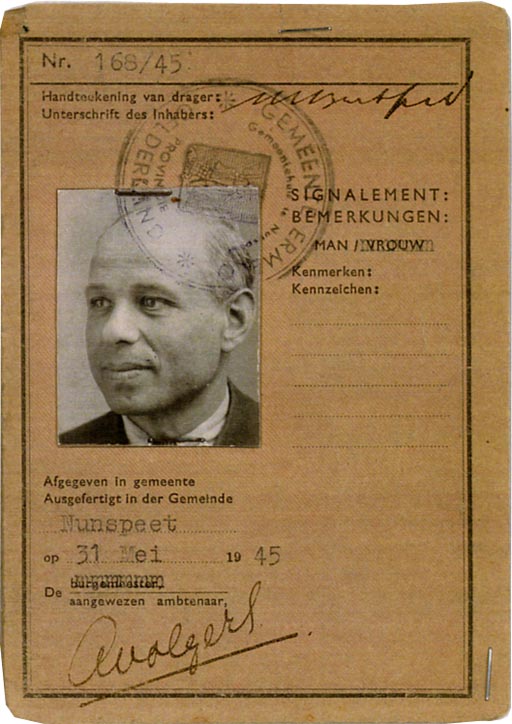

Walter Bartfeld was born in a liberal Jewish family of four. He had a sister called Erni who was three years older. His father Max was originally a wood merchant but after his marriage to Claire Weiser he worked in his father-in-law’s egg business. In reaction to the emerging anti-Semitism in the thirties, the family fled to the Netherlands. Walter’s father could buy a coffee roasting house from a man in The Hague who wanted to move to Hamburg with his German wife.

|

|

|

|

In September 1940, four months after the start of the war in the Netherlands, the Bartfeld family was ordered to leave home and hearth within forty-eight hours. As ‘Volksdeutsche’ they had to live at least 30 km away from the coast.

The occupier made a distinction between ‘Reichsdeutsche’ and ‘Volksdeutsche’. The last group included Jewish refugees but also other anti-Nazi elements. In fact this was one of the first ways to isolate the German Jewish refugees without using the word Jews.

|

|

Father Bartfeld managed to rent the summer house ‘Zonnegloren’ in Nunspeet, far from the village, on the edge of the woods and the heath. Since the Bartfeld’s coffee roasting business would fall into the hands of a German-appointed representative (Verwalter), he sold it to Mr Liesker, a competitor. Mr Liesker proposed drawing up a fake contract of sale. The business would then be Liesker’s and would not be taken over by the Germans. Mr Liesker promised to give the business back after the war.

|

|

After the war, Mr Liesker came to see my father: ‘Here is the key. It is your business.’ He never asked for a single cent for it. He always gave the proceeds of the business to my father. There aren’t many Jews in the Netherlands who can tell that story.

In Nunspeet Walter attended a state school for one more year. After that, all Jewish children had to leave the state school. Since there was no Jewish school in Nunspeet, Walter stayed at home from that day on. Walter’s grandmother and great-grandmother also lived in the family’s summer house. When an opportunity to go into hiding presented itself, it was decided to move great-grandmother Cäcilie Skall to a Jewish home for the elderly in Amsterdam, where she'd be safe. Walters grandmother stayed with the family.

My father was approached in the village by the postman Theo Stevens, who also ran a small tobacconist’s together with his wife. Stevens was the only Communist in the village and as such a kind of a loner in the otherwise Christian village. He said that he could help if we wanted to go into hiding. My father didn’t want to put anyone in danger and suggested placing a caravan far away in the woods.

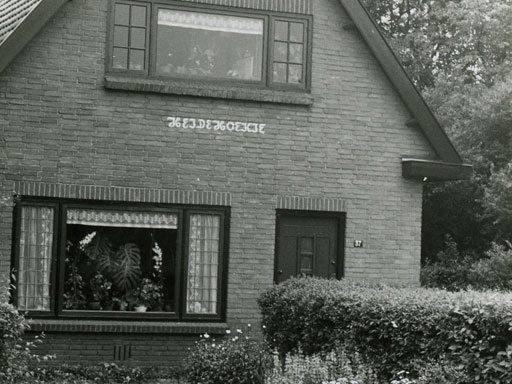

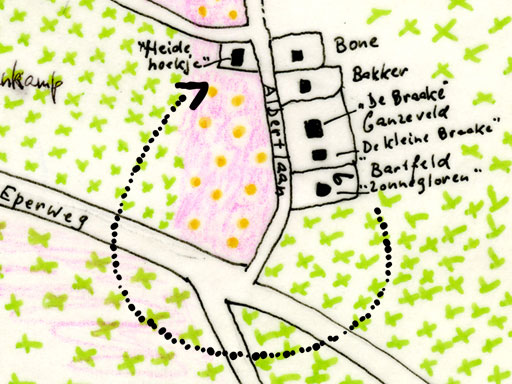

There were five houses in Albertlaan with a fair amount of space between them. At the end of the road, in the house called ‘Heidehoekje’ there lived another German Jewish family from the west of the Netherlands. But they left quite soon afterwards, leaving the house empty.

The other people in the road were a small farmer, a profiteer who bred minks and silver-foxes for the German army, the Wehrmacht, and ‘grandpa Bakker’ and ‘aunt Cor’ who were very soon involved in finding and organising addresses for Jews to go into hiding. The resistance worker Andries Lenstra lived a kilometre further on.

|

|

When the Nunspeet police was ordered to arrest the Jews, the head of police asked for a night respite. The next day he went to the Germans and said: ‘I have sat up all night and read through all the Dutch law books and I have not been able to find an article that would allow me to arrest and collect those Jews.’

Via the Resistance rumours circulated from time to time that the Jews would be ‘collected’. In the night, the family would go to the empty house ‘Heidehoekje’, describing a large circle through the woods, to spend the night there. In the early morning they would return to their own house without anyone having noticed. Four or five times the family went into hiding for one night that way.

|

|

In March 1943 the Bartfeld family were told that it was now getting far too dangerous to stay in the house in Albertlaan. In the night of 23 March they went into hiding.

We dressed very warmly because we couldn’t take anything. No bags or luggage. Or something. Then we went ‘for a walk’. We walked and we walked, and then my father said to my sister and me: “Now listen to me closely, please. We are going to disappear, and from this moment on there are no laws for us any more. There is only one law for us, and therefore for you, too: to stay alive and do everything it takes. But you’re not to harm other people.” And we walked, and we walked, and we walked, until we got to a very thick forest, and suddenly we stood before a caravan that my father had arranged to be placed there.

The days were filled with games and all kinds of jobs. Especially camouflaging involved a lot of work. Food was delivered on a bicycle by grandpa Bakker and aunt Cor.

One day a boy from the village was walking through the woods. I still remember his name and I know exactly who it was. And he bumped straight into the caravan. The danger was doubly great because everybody in the village knew us. It so happened that the resistance worker Andries Lenstra was visiting us right then. He went up to the boy and faced him with a pistol, saying: If you ever say a word of what you have seen..... The boy never said anything, not even to his parents. But Andries Lenstra had given himself away and of course everybody knew him, too.

When an English bomber plane was shot down in the neighbourhood, whereby fragments of it even landed on top of the caravan, it became too dangerous there, because the Germans started looking for the pilots in the forest. The Bartfeld family was collected by bicycle by Mr Von Baumhauer, an Amsterdam lawyer with a house in Vierhouten, and taken to a large, remote summer house.

|

|

The shutters were closed. It was dark and it turned out they were 17 people in it. The house itself was not lived in. Nobody was allowed to know that we were there. We stayed there for about three weeks and we could only speak very softly or not at all.

By telephone people were warned, just in time, for a German raid. In a rush they hid in the nearby heath and from there they saw the Germans arrive and leave again. When it got dark, they walked through the woods in the direction of Nunspeet where they hid in the hayloft in a barn near a farm.

There we lay, at least two nights and days. Without moving. Death in our hearts. We relieved ourselves in our underwear. We could not move. We had not a drop to drink and not a crumb to eat. After two days my father got down from the hayloft and went in the night to Grandpa Bakker and Aunt Cor in Nunspeet. That way he was in contact again with the organised Resistance.

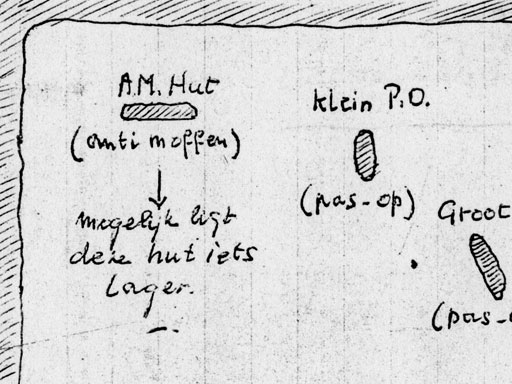

All the people in hiding were taken to another wood in the vicinity of Vierhouten. There was a workers’ shed there, where most of them could sleep. The Bartveld family slept in a tent, together with an engaged couple. Quite soon it was decided to build a log cabin. More and more people arrived to go into hiding, including a number of English and American pilots, a German and an Italian deserter, and an escaped Russian prisoner of war. Ever more log cabins had to be built. One day, a German patrol from Vierhouten came across one of the people in hiding who had strayed a bit further away from ‘the village’. What happened or what was said, was never clear, but not long after the Watch Out Village was surrounded.

After the war the village became known as the Hidden Village.

Those Germans surrounded us but they obviously did not know whether we were armed partisans in the forest or unarmed people in hiding. So they didn’t dare go into the very dense undergrowth. They stayed at a distance and shot into the woods, shouting: ‘Raus ihr Juden, raus’. ‘Out, you Jews, out.’ Darkness fell and all those people, perhaps there were about 60 of them, mainly Jews, fled through the undergrowth in all directions. Fortunately my father knew all the small paths in the forest. Our group – around ten or twelve people, perhaps my grandmother one of them – ran through the undergrowth and the forest, ignoring the shouting and the shooting. We ran for our lives. Eventually, on the edge of the village Vierhouten, we crawled into a hayloft and lay there, a whole lot of us, for I don’t know how long, peeing and crapping without moving.

Eight of the Jews in hiding did get caught, and one of them died in the night. The other seven were shot in the forest the next day. Among them was a father with his six-year-old son. After two days in the hayloft, father Max again contacted Mr Von Baumhauer in Vierhouten.

Walter and his parents were placed with a farming family in Ermelo. The farmer was told that they were evacuees from the surroundings of Arnhem, where heavy fighting was going on at the time.

That farmer and his wife were horribly provocative to us. They probably suspected something. So when we were eating, the farmer sometimes said: ‘If I knew that there were Jews hiding somewhere, I would report them straight away.’ And the farmer’s wife said that we soiled her toilet so badly. Well, we knew better! But it was only to intimidate us, so every time I went for a walk with my parents, we went into the woods and then all three of us would poo.

The farmer and his wife also kept asking why the family never went into the village: ‘There are other evacuees from Arnhem there. Maybe you will meet companions in misfortune there?’ In order to avoid suspicion, Walter and his parents one day walked into the village.

As we walked along, we were recognised by a woman on a bicycle. We stopped in front of a shop window, using it as a mirror to see what was going to happen. A moment later, while we were still standing there, not knowing what to do, the woman came cycling back and dropped a crumpled up scrap of paper. Eventually my father picked it up, and what did it say? ‘If you are in danger, this is my address.’

For a number of weeks, the Bartfeld family stayed with Mrs Cohen Stuart and her two young daughters. Her husband, an officer, was in Germany as a prisoner of war. But it became too dangerous there and they had to leave. People from the Resistance took them by bicycle in the direction of Zwolle, where they separated and individually tried to cross the heavily guarded bridge across the River IJssel.

Then a horse and cart came by and I asked the driver, a farmer, if I could sit with him on the box. That was all right with him. He stopped the cart for a moment and I climbed onto the box beside him. That’s how I crossed the IJssel Bridge. On the way I saw my father walking along, but of course I could not signal to him. And then I saw my mother and my sister. We all four managed to cross the bridge.

The Bartfeld family stayed for a number of weeks in a space that turned out to be also used as a storage place for arms. Because of the great risk, the family was then separated and housed at different addresses in Zwolle.

It was the French-Canadians who liberated us when they entered Zwolle via Wipstrikkerallee – I shall never forget the hour of the liberation – and they came along that long avenue. You saw them coming from afar. They came one after the other on either side of the road, guns at the ready, and ahead of them one single soldier walked in the middle of the road. When he came to us, I ran up to him and said that I was Jewish boy and he was a Jewish boy, too. That was our liberation.

A number of books have appeared about the hidden village:

Het Verborgen Dorp, (in Dutch), written by Jeroen Thijssen and published by Uitgeverij Balans.

Het verscholen Dorp, (in Dutch), written by A.Visser and published by Uitgeverij Bredewold

On 13 February 1945 Grandpa Bakker was arrested, in fact more or less by accident. On 2 March 1945 he was executed by the Germans near Varsseveld, together with 45 others.