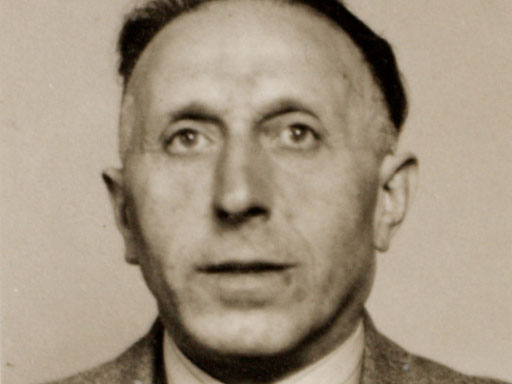

Bloeme came from a Socialist family with four children. Her parents believed in a dignified existence for everybody. Her father, Emanuel was a diamond worker. Her mother was called Roza Emden –de Vries. Bloeme had one sister, Via Roosje. At the beginning of the war Bloeme thought there must be a way of coping with the anti-Jewish measures.

Aren't we allowed to walk in the streets anymore? Okay, so we don't go for walks, so we don't go to the theatre, so we don't go to the library, so we don't go to the shops. I regarded all those measures simply as needling, and as things one could live with. You had to react that way because people who submitted to pessimism went downhill.

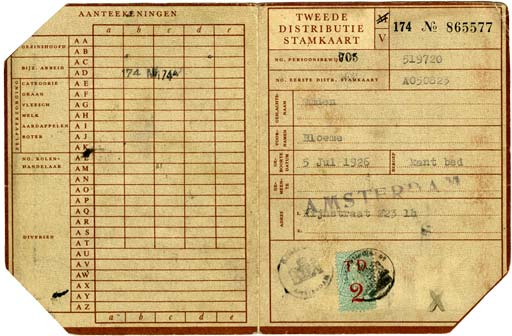

Fear struck when, in 1942, the deportations started and families were torn apart. Bloeme, too, who had just turned sixteen, received an order to report for deportation. Her father, who possessed a Sperre, had managed to get a Sperre for Bloeme as well. But even so, in May 1943 she was called up. Her document had been revoked, made invalid. At that time Bloeme didn’t consider going into hiding. If she didn't turn up, so she had been told, her parents and her sister would be taken in her place.

When we said goodbye, my parents were desperate. From behind the window my little sister waved goodbye, crying. Carrying a shoulder bag and a rucksack I followed the men to the police station in Pieter Aertszstraat, where there were other Jews who'd been rounded up.

Bloeme was taken to the Hollandsche Schouwburg. She managed to enter the building without registering, because she wanted to try and get out of the theatre. If she hadn't been registered no one would miss her. She asked an acquaintance who was serving on the Jewish Council and was supervising in the Schouwburg for help.

A few days later that person came up to me: “Tomorrow you will be leaving. At four in the afternoon a bell will ring. That means all children up to 14 have to meet in the hall. They don’t sleep in the theatre but across the road, in the childcare centre. You will go along with them across the road. Pretend you are one of the supervisors. You will sleep in the childcare centre for one night, and the day after you’ll be gone.

|

|

The plan succeeded and the next morning Bloeme was out and about early. She went to an address in Orteliusstraat. Her parents had written the number of the house in the margin of a letter she’d received from them in the Schouwburg. Bloeme went into hiding with Floor and Truus, who were both very active in the Resistance. Bloeme’s parents spent their last money on a forged personal identification card for her.

In view of the many Resistance activities of Truus and Floor it became too dangerous to keep me in Orteliusstraat. ‘If they catch us, they’ve got you as well.’ They tried to find a new address for me.

Regularly Bloeme stayed temporarily with her boyfriend Freddy who lived with his parents in Rijnstraat. She went there whenever no hiding address was available for her. Freddy’s father was a diamond cutter and had a mixed marriage [a marriage of a Jew and a non-Jew; people in mixed marriages were originally exempt from deportation, but they did have to stick to the strict anti-Jewish measures].

One morning, when I was in hiding there, I was woken up by strange noises. It didn't seem wise to go and look. Freddy's father was a diamond cutter. The Germans suspected him of having diamonds in the house although they should been handed in long ago. They searched the house meticulously, except that they forgot the room while I was lying, dead quiet, while the house search was going on. It was an unbelievable case of good luck.

Bloeme could move to a deserted but fully furnished house on Hobbemakade.

A person from the Resistance brought me something to eat every day and stopped for a talk. It was a lonely place. I felt deserted and miserable.

She couldn’t stay there long because the house would be ‘gepulst’.

This was the address at which Tine and Herman Waage-Kramer formed a centre of the Resistance. In spite of everything the atmosphere was positive.

Especially Tine was very kind to me. And I needed that love badly, because I was suffering from stress. I grew fat so that my clothes began to be tight. I think that's where I must have developed my thyroid condition.

The whole house on Bronckhorststraat had to be cleared in a sudden rush because there was going to be a raid. Everybody got away in time. In the meantime Bloeme was trying to get her younger sister into hiding as well. One of the Resistance workers, Steven, was going to fetch her.

Steven was going to collect her in the evening of 19 June 1943. He came home late, without my sister. He’d had a bad day and was dog tired. ‘Tomorrow morning,’ he said, ‘that's when I'll fetch her.’ Early the next morning, on 20 June 1943, a large-scale raid took place in the southern part of Amsterdam during which all remaining Jews were taken from their houses. My parents and my sister went straight to Sobibor.

A few weeks later the Resistance group was betrayed. Again everybody had to find another place to live quickly. Bloeme was once more temporarily welcome in Rijnstraat.

Bloeme found a job in an old folks’ home on Frederik Hendriklaan. She stayed there for nine months.

I slept in the attic, in a room with three other girls. We each had a bed and a bedside table. One of my roommates was called Ida; she spoke with a soft G [a soft G suggested that the speaker was from the southern half of the country]. She regularly said: “You’re a Jewess. I'm going to report you.” I had no idea how I should react to that.

One night the Germans arrested several patients in their beds. They were the Jewish ones. Bloeme was no longer safe and had to leave again. Once more she found a temporary residence in Rijnstraat.

The Rotterdam Resistance workers Aad and Mary Zegers found Bloeme a job as a housemaid in Rotterdam. She had a room to herself and nobody knew she was Jewish. After two pleasant months there, her employer said to her one morning: ‘Nancy, we are going on holiday for two weeks, and you will have that time off as well.’

I reacted with enthusiasm, but in fact I was desperate. Where was I to go?

Bloeme went to live with Aad Zegers and his sister Mary. One night in August 1944 there was a raid and everybody was arrested.

In the prison called Het Haagsche Veer, where they took us, there were twenty-seven other Jews who had all been supplied with a hiding address by Mary and Aad. So we must have been betrayed by someone from the organisation who knew all the addresses.

Aad Zegers was executed, but his sister was released. Bloeme was deported and went via Westerbork first to Auschwitz and then to Liebau. She survived the concentration camps.

As I climbed the steps of Freddy's family home I was wondering what was awaiting me. Freddy, my boyfriend, opened the door. I was skinny and bald and it was only when I said something that he recognised me. Everything can change, but voices don't. He embraced me and called his parents: ‘Come and look who's here!” They gave me a warm, very warm welcome.’