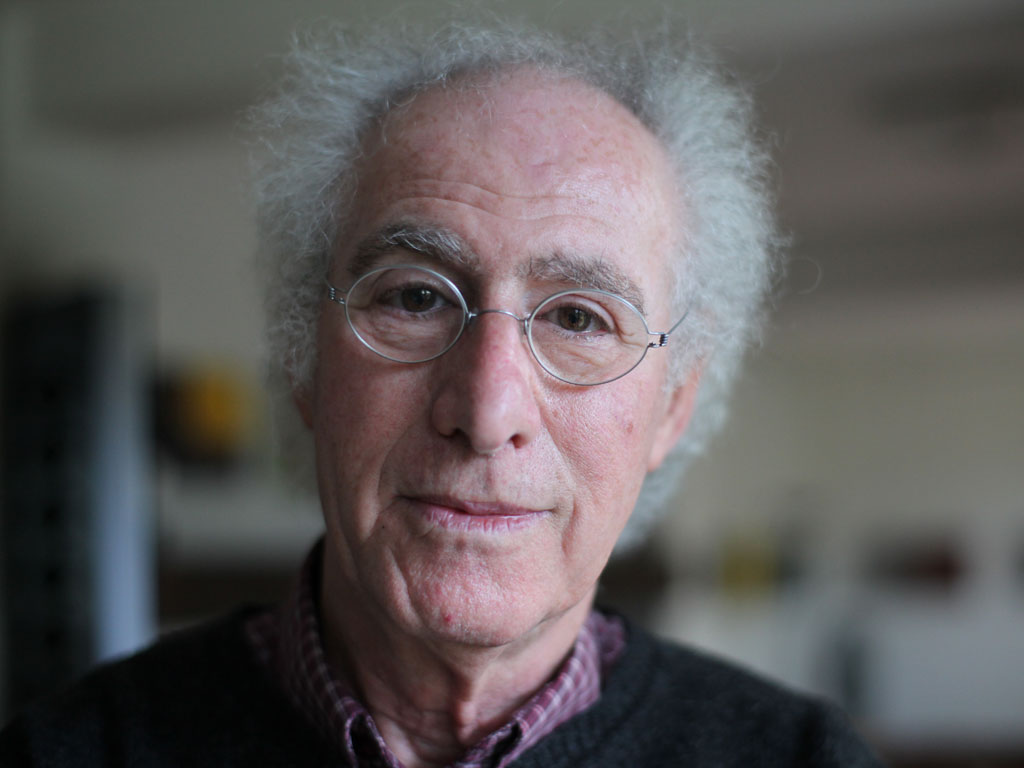

Michel Goldsteen was born into a family of four. His sister Hansje was one year younger. His father, Nathan, had a wholesale business in curtain materials. His mother’s name was Truida Staal; she had studied law. Michel’s grandfather also lived with the family. He adhered strictly to the Jewish laws. That often led to conflicts because father Goldsteen was much more of a liberal.

|

|

When my father came home he had to adapt to the orthodox standpoints of his father-in-law. That regularly irritated him. He was extremely liberal and when not at home would even eat pork.

Michel was seven when the war started. Michel's father's business was taken over by a so-called ‘Verwalter’. In the early years of the war Michel was not really affected by the restrictions inflicted on Jews.

As a young boy I even thought the Star of David was quite exciting. My sister and I sometimes wore our coats inside out and then bought sweets in a shop where Jews were not allowed to go.

Michel’s father had a job with the Joodsche Raad which meant he had a Sperre and therefore temporary protection. He decided to move grandfather to an old folks’ home. He would be safe there; nobody expected that the Germans would also send old people to the ‘work camps’ in Germany.

In September 1942, Guus Schraven, a business relation of Michel’s father’s, came to see them. Suddenly his father said:

You’re now leaving with Uncle Guus, on the train. You're going to go into hiding; it's become too dangerous for you in Amsterdam. From now on your name is Maurice Jansen.

Guus Schraven took Michel to Grubbenvorst where Father Vullinghs found accommodation for many non-Jewish and later also Jewish children from the west with poor farmers. They could use the extra money a boarder would pay. Michel was sent to the Theelen family. They were told that Michel was a city boy who had to recover his health. Michel adapted quickly to the farming life and got on well with the family.

The rest of the family also went into hiding. Father Goldsteen in Helden in Limburg, mother in Zijtaart in Brabant, and his sister Hansje in Helden Beringe. One day Michel’s father came to see him in the house where he was in hiding. They went for a bike ride together.

Somewhere on the way we stopped and sat in the verge. He held me close. There, in that verge, I felt closer to him than ever before in Amsterdam. At the end of the afternoon he took me home. ‘I'll come again soon,’ he said.

Not long after, Michel’s father was betrayed by an ex-employee and deported.

Pastoor Vullinghs thought it was important to inform the Theelen family of Michel’s true identity. It was after all possible that the Germans traced Michel through his father. To be on the safe side Michel was temporarily lodged at the same address where his sister was in hiding, with the Simons family in Helden Beringe. For several weeks he spent night and day in the attic on his own.

There were eight children in the family but only the eldest two knew I was there. In the evening, when the other children had gone to bed, they would come and see me and bring my little sister. It was the high point of the day. I always looked forward to that.

When the Theelen family felt that the coast was clear again, Michel could come back. From 1943 onwards, British bombers on their way to Germany flew over Grubbenvorst. The Germans tried to bring them down. When there was an air raid alarm, Michel, women and other children in the village had to seek shelter in a neighbour’s cellar. The men of the village would be in a dry ditch in order to help pilots if a plane were to crash. This did happen in the night of 24 to 25 June. The house above them came down so that no one could get out.

We sat there until the men came back, and cleared the rubble so that the hatch could be opened. Then we saw the devastation in the village.

Once every two months, Michel's mother came to visit the Theelens. Because the journey by bus was complicated, she often stayed the night.

My mother's visits to the place where I was in hiding belong to the most intense experiences in my life. At night I was allowed to sleep with her in the large bed in the attic. I loved it. The night after, when she had left, I slept on my mother's pillow which still smelled of her. It was a sweet, pervasive fragrance that lingered for days.

After a while Michel's mother stopped coming. She had been betrayed and, like his father, was deported to Auschwitz.

When Michel's mother had been arrested, he was taken temporarily to another address in the same street but a long way on. He now stayed with the Van den Bercken family. Michel knew the family. He had private lessons from the daughter and sometimes he was allowed to go to Van den Bercken’s carpenter’s workshop. But now the situation was too dangerous and for two weeks Michel had to spend the days sitting in a wardrobe.

I sat on a stool, all day long. That was hell. Lying down was impossible, there wasn't enough space for it. Every now and then I could open the little door in the partition for a moment but all I saw was clothes. In that period I was really scared of being discovered.

Michel stayed with the Theelen family until just before the end of the war. They had by then also taken in another Jewish couple. However, a number of Germans were billeted their house which made the situation rather awkward. Grubbenvorst became part of the front line and in the night of 25 to 26 June 1944 the whole village was evacuated. The inhabitants departed in the direction of Sevenum:

It was a cold, clear night. The moon shone on the white ribbons alongside the road which had been laid out by British scouts to show the troops a mine-free route the next day. A small group of men from the village went ahead to let the British know that the people coming were not Germans but people from Grubbenvorst.

After the war, Michel and his little sister were lodged with a family in Utrecht. Hardly any members of his family returned.

Originally we didn't assume that our parents had both been killed. We kept being hopeful. That wasn't unjustified: years after the war people still came back from the east. Slowly we got used to the idea that they would never come back.