|

|

Hanneke was four years old when the war broke out. Her father was in the air defence. She has few memories of him. “In those early days in May 1940, we went to see him. I sat on the back of my mother’s bicycle. A German plane flew over low. They were shooting at people. My mother threw her bicycle on the ground and pulled me into a ditch. For me that’s how the war started.” Hanneke was vier toen de oorlog uitbrak. Haar zat bij de luchtafweer. Ze heeft weinig herinneringen aan hem. ‘In de meidagen van ‘40 zochten we hem op. Ik zat bij mijn moeder achterop de fiets. Een Duits vliegtuig vloog laag over. Ze schoten op mensen. Mijn moeder gooide de fiets op de grond, en trok mij mee de greppel in. Zo begon de oorlog voor mij.’

The Jewish faith hardly had a place in Hanneke’s home. But when the Star of David became obligatory by the end of 1941, being Jewish did start to play a role in her life. “I wasn’t allowed to go to the swimming pool anymore, wasn’t allowed to visit the zoo with my grandfather and grandmother and it was forbidden to play school outside in the streets with the other children from the neighbourhood.”

Hanneke’s father had a printing press together with her grandfather: Lithografie Lankhout. But Jews were no longer allowed to own their own businesses. A so-called “Verwalter” was installed. A pro-German Aryan Dutchman took full control of the company.

Once the situation started to become more and more dangerous for the family, Aunt Zus (Ru Paré’s alias, an artist and family friend who worked for the Resistance) offered to help find addresses where they could go into hiding. “One day, in the spring of ’42, my mother said to me: ‘Hanneke, you’re going to stay with other people. Here, in The Hague, you can’t play outside anymore. You’re going to go up North, there aren’t so many Krauts/Jerries (kies welke term je wil; dit is natuurlijk een soort slang) there, so you’ll be able to play outside again.’”

Hanneke’s mother went into hiding in Limburg and an address for her brother was also found in Limburg. “My father decided he wouldn’t go into hiding.” “I can’t hide out in some attic”, he said to my mother. “I would be a danger to myself and to others.”

Aunt Zus took Hanneke by train to Ter Apel. “We found ourselves in a compartment with eight other people, in two groups. The train was on its way and I said: ‘Aunt Zus, I’m outside and there’s no yellow star on my jacket, that’s against all the rules, isn’t it?’

‘Hanneke’, Aunt Zus said immediately, ‘we’re getting off at the next stop, we’re there.’

First lesson about going into hiding: ‘Never ever say anything about your star, because then they know you’re Jewish. And the Germans are looking for Jews and they will shoot and kill you.’ That was the very first time I really understood the meaning of danger.”

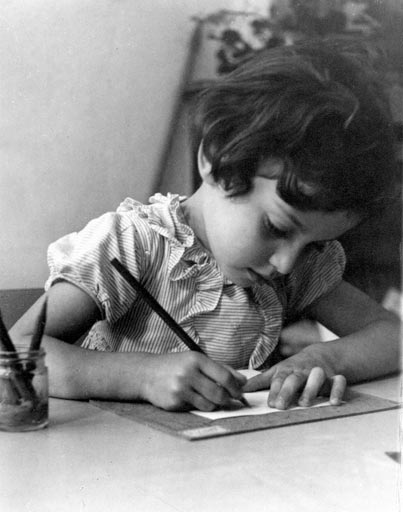

In Ter Apel, Hanneke was allowed to be outside again. Because she was so proud that she could already read, she would read aloud to the other children. This did not go unnoticed.

They called Aunt Zus on the phone. “Hanneke”, she said, “it’s nice you know how to read, but you mustn’t read aloud to the other children anymore. Children who know how to read at the age of six stand out too much.” This is also when Hanneke’s thick dark curly hair is bleached.

|

|

All in all, Hanneke moved twelve times. Every time she was given a new last name: “They were wise enough to keep Hanneke as my first name. There were all these variations of my last name: Lankhout, Lankhorst, Langedam, Lankhuizen, I must have had every possible existing name that started with “La”.

Aunt Zus would teach Hanneke a new back story every time she was moved and urged her strongly to forget where she came from. On their trips they would rehearse the story so well that Hanneke had no problem retelling the story naturally.

The hardest thing for Hanneke was always having to be “nice”. One time, when she was staying with a pastor’s family, that became a problem. Hanneke stayed downstairs in the cellar; she was only allowed upstairs for the Sunday meal. Steak was served. “After the pastor had neatly sliced and divided the steak, I asked him: ‘Pastor, you’ve told me about Jesus. Didn’t he say everything should be shared fairly? Then why have you kept the largest slice of steak for yourself?’

The pastor was furious: ‘You, ungrateful Jewish child, you haven’t understood a thing I taught you, how dare you?’

From May 1944 until they were liberated on September 17, 1944, Hanneke was in hiding in Eerde near Veghel. Father Verhoeven - one of Aunt Zus’ contacts - took her to Uncle Jan and Aunt Joske. They had only just recently married and Aunt Joske had already had two miscarriages. At first, they were not very enthusiastic about taking in a child. Father Verhoeven said: ”This little girl is in terrible danger. She needs help. If you take her in, all of the nuns and myself will pray Joske won’t have another miscarriage.” A few months later, the baby, Regientje, was born.

“I was allowed outside again, I went back to school and my hair no longer needed bleaching. That was nice, because bleach really stung your eyes. The first time I arrived at my new class, the teacher, Miss van Bult said: “We have a new little girl in our class. You should all try to be nice to her, because the poor thing lost both of her parents, they were killed when Rotterdam was bombed. She’s an orphan and has no parents. Now she’s come to live here.”

Hanneke once had to sleep with the dog in the dog house because there was a rumour going around that houses were going to be searched. More people were in hiding in Eerde.

On her mother’s birthday, Hanneke was allowed to write her a letter, Aunt Zus would take the letter to her mother. “At the bottom I wrote: “Houdoe*, Hanneke”(* colloquial, regional bye-bye - translator - kun je misschien helemaal onderaan zetten). My mother received the letter without a place or date, Aunt Zus had carefully cut that part off.”

On Sunday night, September 17, 1944, heavy fighting broke out. Hanneke escaped with Aunt Joske to Veghel. “I sat on the back of the bicycle facing backwards and held onto the baby’s pram with Regientje lying in it. When the planes flew over, we jumped off the bicycle and crawled into a sewer pipe. That is how we escaped to Veghel.”

After they were liberated, Hanneke spent some time at a farm in Mariaheide very near Veghel. One afternoon she was outside playing with the other children the yard. “From the corner of my eye, I saw this unknown woman approaching. The woman threw her bicycle onto the ground and called out: ‘Hanneke!’. I immediately recognised her voice. That’s when I knew: the war is truly over. My mother has come back.” Her mother had found Hanneke due to that specific word “houdoe” that people say in parts of Brabant. She went to all of the parsonages to find out if they knew a Hanneke.”

“In Veghel, the pastor said:’No, there’s no Hanneke living here. But there is a Hanneke in Eerde. But now there’s no one there anymore, the whole place was destroyed. Most of the people from Eerde are now in Mariaheide.’ My mother found me thanks to that code word “houdoe”.

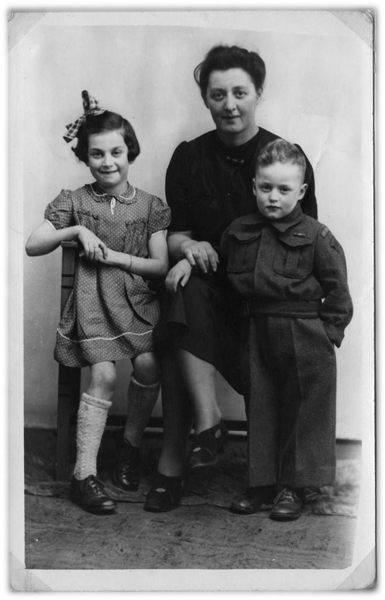

Hanneke’s little brother, Paul, was in Grubbenvorst, Hanneke’s mother knew that. He also came to Veghel.

Paul didn’t like it there, he had gone into hiding at the age of two and was taken in by a large family with seven children and lots of chickens and cows. At some point, he said:”Hanneke, I can believe you’re my sister, but what about Mom? Did Mom buy me from Mother?”

|

|

Hanneke’s father didn’t survive the war. He tried to join the Engelandvaarders, but was caught along the way.

“Even later on, when I was back at school in The Hague, I still always believed he’d come back. The Russians were holding him as a prisoner of war. Or he’d ended up in a camp and was liberated by the Russians.

One day my mother gave me my father’s last letter, that he’d posted from Paris. He writes about the chain of resistance workers, that time and time again is broken somehow. And he writes about sleeping on a bench at the station. That letter had been delivered through Aunt Zus to my mother. At the end he writes:” This might be my last letter.”