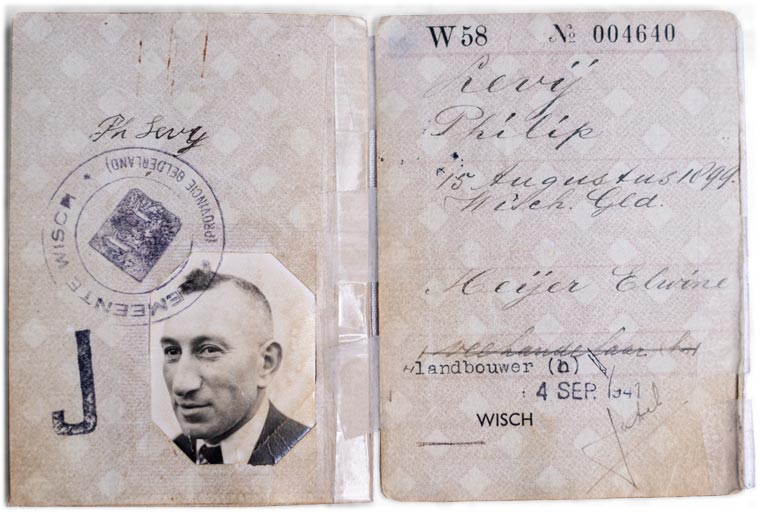

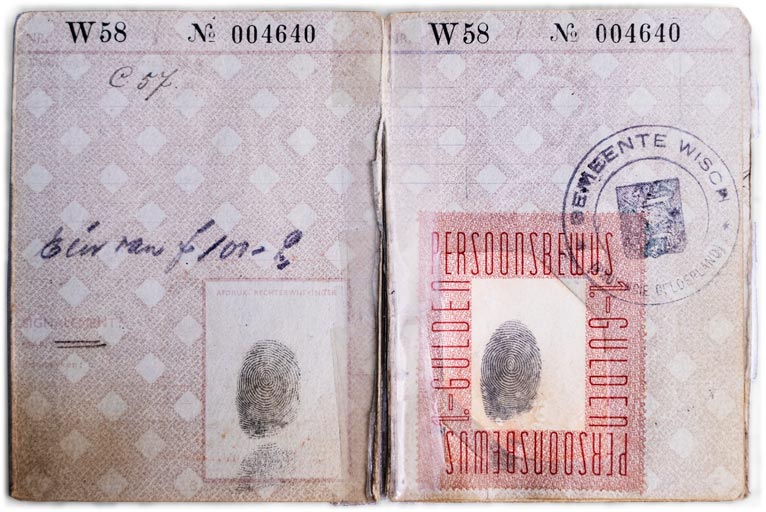

Joop Levy was born in 1935 in Varsseveld in the province Gelderland. His father was a cattle trader in an area of Holland known as the Achterhoek, as were two of his brothers. Before the war there were many Jewish cattle traders in the Achterhoek, some of them had butcher shops as well. “Being a cattle trader wasn’t exactly a rich man’s profession. My father would go off every morning on his bicycle, rain or shine, literally from farm to farm to see if the farmers had anything to sell or wanted to buy from him.

Joop is an only child, the only son. “I never asked my parents, but I suspected that the threat of war was the cause of their not having more children. My mother was originally from Germany, from Trier. Before the war broke out, she was very much aware of what was going on there.”

The relationship between Varsseveld’s Jewish and Gentile population was good. “I never really experienced antisemitism. Varsseveld was a “Jüdenfreundlich” town, I often used to say.”

The Levy family were not orthodox Jews. “In the entire Achterhoek region there were hardly any orthodox Jews. We kept to a few general rules and habits of the Jewish faith, for instance, we didn’t eat pork.”

At some point during the war, Jews were ordered not to attend their own schools and a Jewish school was set up in Winterswijk. “It wasn’t much bigger than a classroom, and twelve to fourteen children from all over the Achterhoek would go to this school where we were taught by a Jewish teacher. That’s when it really sunk in that I was Jewish.”

On the afternoon of Thursday, September 24th, 1942, Joop had come home by train from Winterswijk when his mother told him he would be being picked up in an hour and a half by Willem ter Beek, one of his father’s Gentile colleagues. My mother said: “Ter Beek is going to take you on the back of his bicycle somewhere and I will join you later.”

Joop’s father, being a cattle trader, knew many farmers in the area. He had asked the Hofs family, who lived between Varsseveld and Aalten, if they would shelter us. Hofs answered: “I’d like to, but I only have room for one person.” There turned out to be six young men in hiding who weren’t Jewish at his farm, in the ages of 18 to 30, who had been called up for the Arbeitseinsatz. On top of that, the eldest son, Wim, was the leader of a Resistance group. My father went into hiding with Hofs and my mother and I went to the Ebbers family in Lintelo.”

|

|

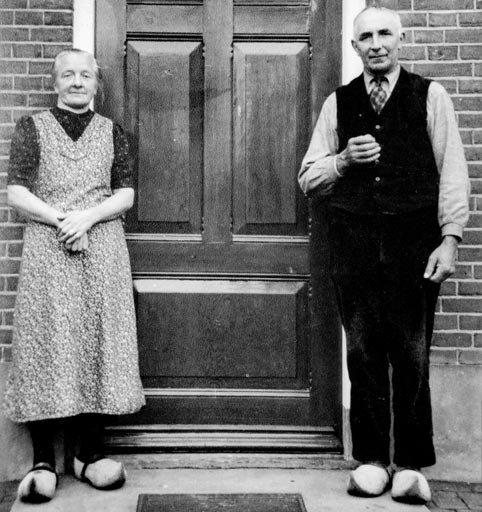

In the weeks before they went into hiding, the Ebbers’ daughter regularly came by to pick up some of their belongings. “When I arrived that Thursday evening at the Ebbers' home, I’ve been told I said: ‘Oh, do you live here, Leida?’ Later on, that same night, my mother arrived.”

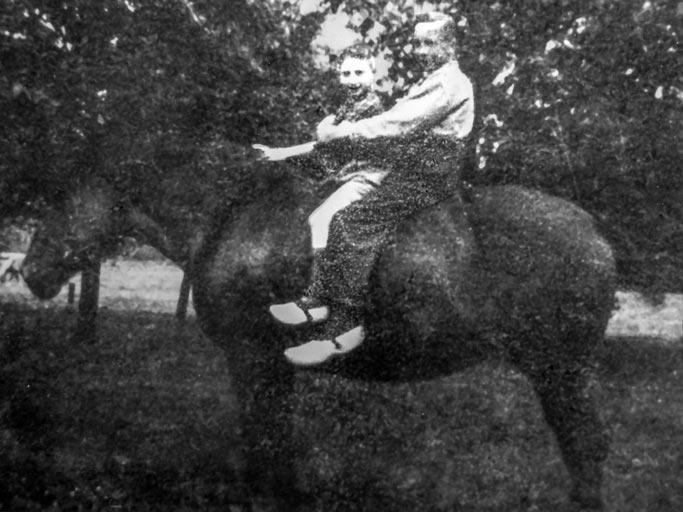

Joop wasn’t allowed to play outside, but if there was no immediate danger, he would sometimes help farmer Ebbers feed the pigs. And in the beginning, Joop and his mother would go for a stroll once it was dark. Later on, this was no longer possible. In the beginning, they slept in a normal bedroom, but that, too, soon became too dangerous, because most razzia took place after nightfall.

Joop wasn’t allowed to play outside, but if there was no immediate danger, he would sometimes help farmer Ebbers feed the pigs. And in the beginning, Joop and his mother would go for a stroll once it was dark. Later on, this was no longer possible. In the beginning, they slept in a normal bedroom, but that, too, soon became too dangerous, because most razzia took place after nightfall.

The farmer built them a hiding place in the hayloft above the horses’ stable. It was like a small wooden room in which you could only sit or lie down in.

Joop:” When you were up in the hayloft, all you could see was a large haystack. In the wooden ceiling in the horses’s stable, he had sawed through the cracks between the planks to make a hatch. Whenever we needed to go up into our hiding place, we would put a ladder against the wall in the stable and climb up into our sleeping space.”

In the meanwhile, Joop’s father had joined them at the Ebbers’ farm. Hofs had a feeling that things were becoming too dangerous at his farm. Farmer Hofs turned out to be right, he was later betrayed, the men in hiding were discovered and his son, who had led a Resistance group was executed by a firing squad. The Ebbers’ 23 year-old son could have been caught during a razzia and sent off to a work camp in Germany. He slept in the hayloft hiding place, too.

|

|

The family Ebbers’s farm was situated a bit off the “main road”, hidden behind a small stretch of trees. “It’s quite possible the Germans overlooked the farm. However many razzia took place after people had been betrayed. That never happened to us.”

Joop: “I had three Jewish cousins in Varsseveld - all three of them much older than me - they were in hiding, too. They went into hiding with the Geurink family in Lichtenvoorde and stayed there with a deserted Russian pilot. My oldest cousin and this pilot made a wonderful wooden airplane model for my eighth birthday. Because there weren’t many building materials available, most of the plane was made from an old wooden toilet seat. Willem ter Beek brought it to me.”

In early March 1945, from one day to the next, the farm was requisitioned by a platoon of German soldiers who had retreated from the Ardennes. “They were filthy and covered in lice. After they’d washed themselves and eaten their bellies full, they would go up to the hayloft to sleep. They slept in the hay on top of our little hiding place.”

“We had to keep perfectly still and not make a sound, and all we could do was lie flat on our mattresses or sit on our haunches. There was a small window in the stable, that was partially visible in our hiding spot. During daytime, we could see a narrow strip of sunlight so at least we knew whether it was night or day.”

After a fortnight, the Germans left. They did take two of farmer Ebbers’ horses with them.

Then, after about another fortnight, on March 31st, the Canadians liberated the Achterhoek.

“I can still remember farmer Ebbers saying, in his Achterhoek accent: ‘You can go outside again, because now you are free.’ That literally felt tremendously liberating.”

The Ebbers family were truly exceptional. During the period they sheltered us, Joop’s father had asked them several times how much he owed them for their food and board. The farmer would always say: “We’ll see about that when the time comes.”

After we had been liberated, my father said to him: “And now you have to tell me how much I owe you.” “We’ve all managed to survive,” farmer Ebbers said,”you’ve never given us any trouble, so that covers whatever you owe us.”

During the time they were in hiding, Joop often spoke about his best friend, Joop Becking, a little Gentile boy: “I hope he’ll play with me again, when the war is over and we’re liberated.” When we saw each other again on April 1st, 1945 in Varsseveld, it was as if I’d never gone away. We immediately hit it off again and were friends just like before. And we remained friends till his death on May 2nd, 2021. We’d always call each other “Junior”. I don’t really know how that name came about. At his funeral, I said my goodbyes to him with the words: “Dear Junior, my great friend, rest in peace.”

During the time they were in hiding, Joop often spoke about his best friend, Joop Becking, a little Gentile boy: “I hope he’ll play with me again, when the war is over and we’re liberated.” When we saw each other again on April 1st, 1945 in Varsseveld, it was as if I’d never gone away. We immediately hit it off again and were friends just like before. And we remained friends till his death on May 2nd, 2021. We’d always call each other “Junior”. I don’t really know how that name came about. At his funeral, I said my goodbyes to him with the words: “Dear Junior, my great friend, rest in peace.”