Mattie’s father was originally from Sokolov, a small town in Poland. Mattie’s father moved to Düsseldorf when he was three years old with his parents and around 1934 when he was 25 years old, he and his brother moved to Maastricht. Mattie’s father started a “lay-away business” in Maastricht; they sold textiles to mineworkers on a lay-away plan.

Mattie’s father was originally from Sokolov, a small town in Poland. Mattie’s father moved to Düsseldorf when he was three years old with his parents and around 1934 when he was 25 years old, he and his brother moved to Maastricht. Mattie’s father started a “lay-away business” in Maastricht; they sold textiles to mineworkers on a lay-away plan.

Mattie’s mother was from an orthodox family. Her father was a teacher, butcher and worked for the Jewish community in Maastricht. Although Mattie’s grandfather wasn’t officially a rabbi, in practice, he was. His grandparents lived next to the synagogue where Mattie used to play a lot when he was little. “On Fridays, all of the Jews would go to market to buy chickens. My grandfather would then slaughter them according to kosher laws. Every now and then, there would be chickens that kept on flapping and flying about; one time one of them flew up in the air and landed on the roof in the gutter.”

Mattie’s mother was from an orthodox family. Her father was a teacher, butcher and worked for the Jewish community in Maastricht. Although Mattie’s grandfather wasn’t officially a rabbi, in practice, he was. His grandparents lived next to the synagogue where Mattie used to play a lot when he was little. “On Fridays, all of the Jews would go to market to buy chickens. My grandfather would then slaughter them according to kosher laws. Every now and then, there would be chickens that kept on flapping and flying about; one time one of them flew up in the air and landed on the roof in the gutter.”

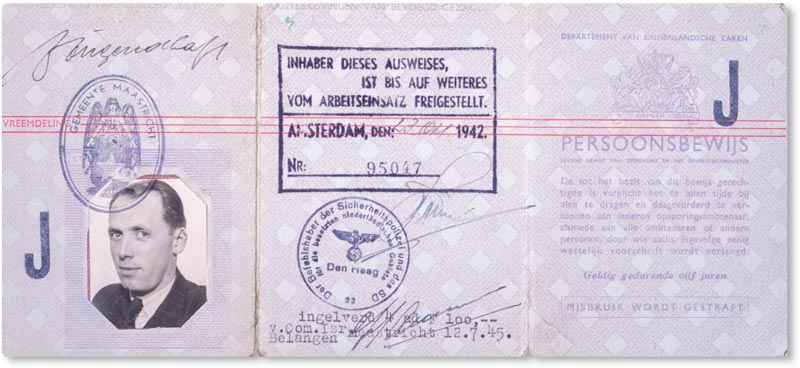

Mattie was five years old when he went into hiding. His family was late in seeking refuge. The Jewish community had appointed his father as a spokesperson in their dealings with the Germans. The family had a “Sperre”, a temporary exemption from deportation. The Tugendhaft family were therefore one of the very last families in Maastricht to go into hiding.

|

|

“The rucksacks were already packed, but at the very last moment, when the situation became critical, they had no place to go. One day, when my father had gone to the post office to send off a package to family in Westerbork, a man tapped him on the shoulder.

“I see that you’re Jewish”, the man said - my father wore the Star of David. “Are you allowed to walk freely in the streets?”

“No”, my father said, “not really.”

“Shouldn’t you go into hiding?”

“Yes”, my father answered, “I’d like to, but I don’t have anywhere to go.”

That’s when the man said:”I’ll come to your house tonight.”

A long time after the war, it became clear that this man was a member of Jo Lokerman’s Resistance group. Mattie:”The entire group was betrayed by a whore who was sleeping with the Ortskommandant in Maastricht.”

On one of those evenings, Mattie and his sister were sitting on their father’s lap.

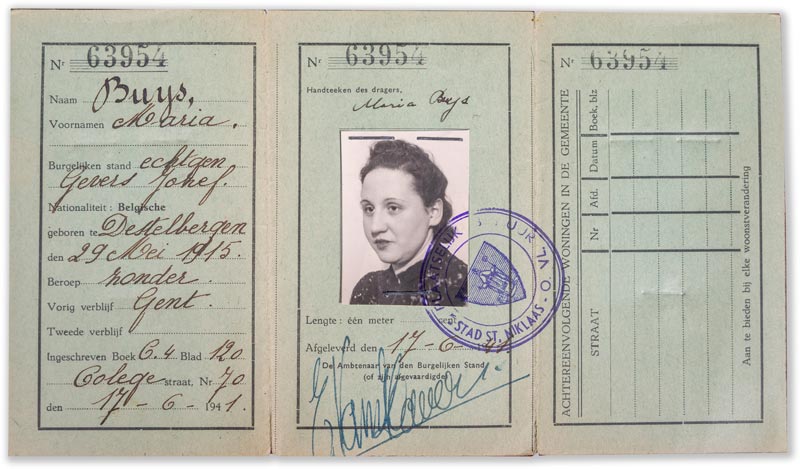

“We’re going to have to go away for a while”, my father told us, “because there are German soldiers and these German soldiers want to kill us because we’re Jews.” “I had to change my name, but I was allowed to choose the name myself. There was this nice little boy in kindergarten and his name was Mattie. I liked that name.” His last name became Gevers, just like his mother’s new last name.

Mattie always kept his new first name (alternatief: Mattie always kept Mattie as his first name after that), by the end of the war he had gotten used to it. Mattie’s sister was taken in by a household help who had a sister in a Flemish nunnery. Mattie’s parents were in hiding with the Koole family, a well-known pastry bakery in Maastricht where the Germans would go and eat pastry for free. Mattie’s baby brother, Bennie, was born there.

Mattie was picked up by “Aunt Nellie”, a go-between who brought him to approximately ten different hiding places in the south of Limburg during the war. Except for one place in particular, Mattie had it relatively well while he was in hiding.

The exception was with a family on a farm in De Weerd, a small village along the Maas river, not far from Roermond. “I was treated terribly and abused there, something Nellie never knew.”

Mattie slept in the same room as the other children, two sons and two daughters, who were much older than he was.

“Every morning around five, the farmer’s wife would go out to milk the cows. One day, the farmer dragged me out of bed and took me up into the attic and made me run around in circles, completely naked. At some point, he grabbed me by the neck and hung me from the rafters with a piece of rope until I was barely conscious. ‘When the Germans get their hands on you’, he said, after he took me down, ‘that’s what they’ll do to you.’”

All of the abuse and torture this man inflicted on him instilled a terrible fear in Mattie, he was terrified of being left alone with him. But the family, too, weren’t completely innocent either in the abuse Mattie suffered. “One day, they tied me to the back of a calf and let the calf jump up and down in the field. I was dangling behind the calf and broke my leg. The family stood there and laughed.”

The farmer also once took Mattie to a ditch at the end of their field, near the Maas river. “There I was, in the middle of winter, wearing only my underpants. That wasn’t very pleasant. He held me down in the water and practically drowned me.”

When Mattie’s ear had become infected, the farmer tried to cut the infection open with a breadknife. “He ruined my ear, after the war a plastic surgeon had to repair what was left of it. The infection was still there, it was completely ingrown.”

The farmer’s wife contacted Nellie, the go-between. Nellie took Mattie to her own home in Maastricht, because she didn’t immediately have another place for him to stay. One evening, during curfew, the resistance group that arranged the hiding places let Mattie’s parents visit him. “It was terrible for them to see me like that, with my ear all a mess. I’ve been told that I couldn’t stop crying. I wanted to stay with my parents, but it was impossible.”

Afterwards Mattie was taken to “Aunt Mien” and “Uncle Albert” who took him in and cared for him with a great deal of love and affection.

On September 17, 1944, Klimmen was liberated. Mattie’s parents came straight away to see him. “There they were suddenly, standing in Aunt Mien’s garden, I was playing inside a little tent. Aunt Mien became very emotional, she had no children of her own and she was very attached to me. My parents decided to leave me there for a day or two longer so that the Lemlijn family could get used to the situation.

The Tugendhaft family managed to survive their time in hiding relatively well. “My parents and grandparents survived. And so did my baby sister Trinette. When she came back home, she no longer recognised my father and mother and we couldn’t understand her. She only spoke French. My younger brother, Bennie, was the very first Jewish baby boy to be registered with the municipality after the war.”

The Tugendhaft family managed to survive their time in hiding relatively well. “My parents and grandparents survived. And so did my baby sister Trinette. When she came back home, she no longer recognised my father and mother and we couldn’t understand her. She only spoke French. My younger brother, Bennie, was the very first Jewish baby boy to be registered with the municipality after the war.”

The rest of the family, on his mother’s side, the De Liver family were all murdered.

Mattie’s father later went to all of the places that had taken us in in order to pay what he owed for food and lodging. Almost no one wanted any money. Except for the farmer who had abused him. “He wanted to buy himself a new farm with the money.”

“My mother never wanted to believe the stories about how he tortured me.

‘A person can’t be that bad', she would say. ‘It’s a bad dream. It’s nothing but a bad dream.’ That always really upset me. She just wouldn’t believe me.”

Decades later, Mattie went with his good friend Jos from Roermond to find the exact place where he had been in hiding. Jos, who knew the region well, suggested they go to the local café in De Weerd. The people who owned the café in De Weerd had gone to great lengths to help Jews find hiding places, they might know something. Naturally, these people had died many years ago. The daughter, who was by then in her eighties, still ran the establishment, maybe she knew something.

“Yes”, she said, “there was a little Jewish boy in hiding there who was terribly abused.”

“I felt a cold shiver run down my spine. This was the moment that my abuse was finally confirmed and recognised. ‘That little boy, that was me.’”