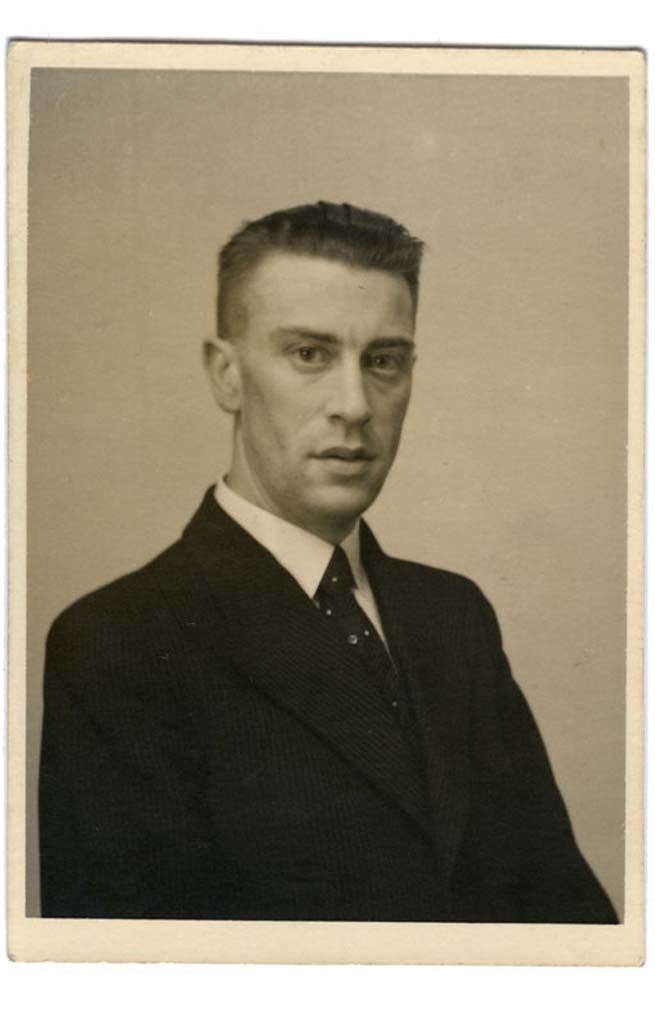

Johan Sanders grew up in an orthodox Jewish family who observed the Jewish laws. He had two sisters, Lenie and Tilde. His father, Gerard, was an executive secretary with a large textile company.

On the Sabbath we went to the Shul, relatives came to see us or we visited other relatives ourselves, always on foot because cycling or driving a car was not allowed on the Sabbath.

|

|

When the war broke out, Gerard Sanders became secretary of the Joodsche Raad in Enschede. The President of the Jewish Council in Enschede, Sig Menko, felt that he should advise the Jews in the town to go into hiding. This was contrary to the official policy of the Jewish Council Amsterdam.

At some point Sig Menko stood up: ‘Gentlemen, we can advise our people only one thing: go into hiding.’ Instantly Mr Cohen and Mr Asscher suspended the meeting with the words: ‘The subject cannot be raised here. The words go into hiding are not part of our vocabulary.’

Gerard Sanders was fully aware of the situation in Germany because he heard the stories of the many Jewish refugees from across the border. He was convinced that they would have to go into hiding to survive.

On Friday 9 April 1943 the Sanders family decided to go into hiding. An important role in organising this for them was played by Reverend Leendert Overduin who went on to help many others. Johan and his two sisters ended up in Veenendaal. Johan stayed with the Engelenburg family on Benedeneind.

|

|

|

|

The house was on De Grift, a canal that separated Stichts Veenendaal and Gelders Veenendaal. There were several little boats in the water and it was lovely to rock them to and fro. The very first day I fell out and went right under in the duckweed. I had to go back to the house. The only thing I managed to say to Mrs Engelenburg was: ‘I was practising hiding under water’. She laughed: ‘You shouldn’t have gone into that boat and you shouldn’t have rocked it.’ She treated me like her own child.

Johan Sanders then had to call himself Johan van de Berg from Rotterdam. The story was that his mother had died during the bombing of Rotterdam and that his father was not able to look after him. At school and in the street he would regularly come across his sisters and he tried to keep in touch with them inconspicuously. Officially he didn’t know them and he was not allowed to talk to them.

In August '44 an angry farmer claimed that Johan and his friends had walked across his land and that he had let his chickens escape. To avoid all risks he was taken to another address the same evening. There he was not allowed out of the house.

I had to stay indoors and I spent all day reading. But they couldn’t get too many boys’ books from the library because that would attract attention.

He wasn’t even allowed to stand at the window and look out, because there were NSB people, collaborators, living next door who might see him. When Johan got the chance to move to another address, he did.

In Wageningen Johan stayed in a boarding house where there were other Jews in hiding. When the airborne landing took place, on 17 September 1944, they were evacuated from Wageningen.

Then came 17 September 1944: the airborne landing at [this was Operation Market Garden, a major Allied attack). From Wageningse Berg we saw how, across the Rhine, soldiers came down from the sky, and war material, bicycles, ammunition. Just grin and bear it and the war will be over. We thought!

He was then placed with a minister’s family in Bennekom.

Because of the fighting Reverend Boer and his family had to move several times yet. Johan didn’t feel at ease with them. He didn’t get on too well with the minister’s son, Jacob. Also, the minister was rather loose-lipped with the elders. That made Johan feel very unsafe. When the war was over, Gert van Engelenburg came to fetch Johan on a bicycle.

Close to the house he nudged me: ‘Look, there’s your mother.’ She’d grown older, I’d grown older. You want to hug one another. I tried to hold her, she tried to hold me. Emotionally there just wasn’t anything for a while, certainly not that feeling of elation I’d been hoping for.

Johan’s father did not survive the war. On the way to the address where he was going into hiding he was arrested by the SD, probably betrayed. The date of his death was set at 28 February 1945. He was last seen in Camp Groß Rosen. Johan’s sisters did survive the war.