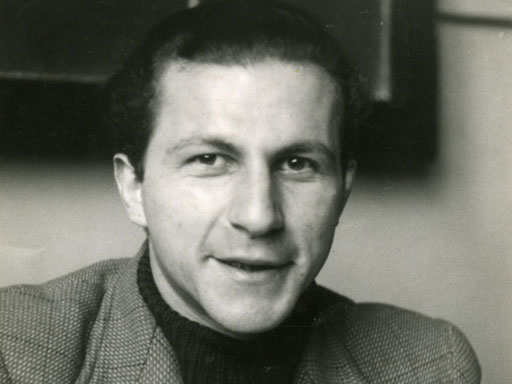

Lous was an only child and was born just over a year after The Netherlands were occupied. Her father, Louis Hoepelman was a teacher married to Rosa Kwieser.

Rosa worked as an administrative assistant for the Bijenkorf department store. Both she and her husband were members of the Communist Party before the war. After the war broke out, they joined the Resistance and amongst their other tasks were responsible for the printing of pamphlets used to promote the general February Strike and the illegal publication/paper De Waarheid (The Truth).

|

|

They all went into hiding together early on in 1941. At first, they stayed with the painter Henk Henriet, but soon moved to separate places for safety purposes. Mother Rosa (Ro) Kwieser was in hiding at several addresses, one of which was the house of the famous sculptor Mari Andriessen in Haarlem while Louis stayed on in Amsterdam in the Pijp neighbourhood where he was eventually betrayed.

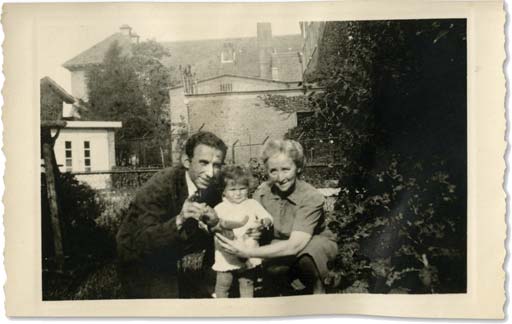

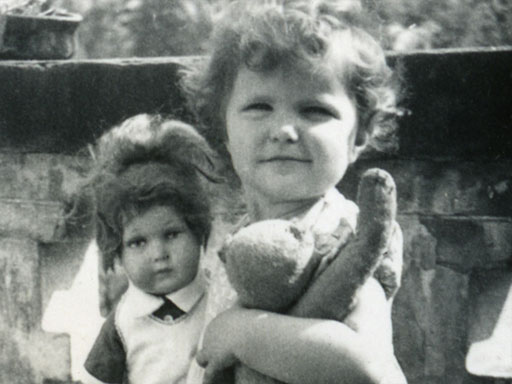

Lous was taken to one of her father’s half-brothers in Bussum and put into hiding. Her uncle Saam Hoepelman was married to Aunt Rie. Aunt Rie was not Jewish. Jews in “mixed” marriages were normally not called up for deportation. Uncle Saam and Aunt Rie didn’t have any children of their own and raised Lous as if she were their own. They even thought they were better suited to raising Lous than her own mother which caused quite a bit of tension after the war. Mother Ro tried to visit Lous at least once a month while she was in Bussum.

Germans regularly passed through the neighbourhood where Lous was in hiding.

I guess I was about 2 and 1/2 or 2 and I’d go outside and march alongside of them. These Germans thought I was very cute and then I heard Auntie tell the story of how they would say I looked like the husband, but had the wife’s eyes. That’s what those Germans said to her. Well, of course, she just beamed with joy that the Germans, too, thought I was their child.

|

|

|

|

By 1943 things were becoming far too dangerous for Uncle Saam as well and he, too, had to go into hiding. Soon after, Lous’s mother took her to a place in Amsterdam where she was betrayed. She ended up in the prison on the Weteringschans. There was a lady there, a Mrs. Adriaansz , who took Lous under her wing and kept keeping an eye on her once she was sent on to Westerbork. Because no one knew who Lous’ parents were or where she came from, she was placed in Westerbork’s orphanage.

In September 1944 the orphanage was cleared out. All 51 children were put into cattle carts with destination Auschwitz. Oddly enough, the train ended up going to Bergen Belsen. The journey took three days. One child, a three-month old baby, died. Mrs. Adriaansz still kept on looking after me. After two months we were back on a transport, this time with destination Theresienstadt.

In 1945 this entire group of “unknown children” were liberated by the Russians. One of mother Ro’s friends from the Resistance, Henk Ladiges, had received a message from The Red Cross that a group of children, orphans, were waiting in Theresienstadt for transportation to The Netherlands. Lous turned out to one of those children. Lous, suffering from bronchitis, scurvy and double pneumonia arrived back in Holland at Valkenswaard where her mother awaited her.

The Red Cross advised to have me sent to Switzerland due to my poor health so that I could regain my strength at a so-called “Erholungsheim”. Another transport, once again no warmth, no family. When I came back, all I spoke was German. I was greeted by a woman who told me she was my mother. She was with a man called Uncle Hans. Later on, I called him “Papa” instead of “Uncle”. Hans thought of me as his own daughter and was very kind to me.

Daphne Meijer has written a book about the group of unknown children titled Unknown Children. The Last Train from Westerbork..